|

by Philip Price Director: Robin Wright Starring: Robin Wright & Demian Bichir Rated: PG-13 Runtime: 1 hour & 29 minutes I've never seen an episode of Bear Grylls' “Man vs. Wild,” but I imagine “Land” is more or less what that show would feel like if shot by Emmanuel Lubezki and scored by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. That isn't to say Robin Wright's feature directorial debut is devoid of anything substantial or has nothing to say (I'm sure “Man vs. Wild” can be illuminating in many ways), but more that the simple narrative of a bereaved woman seeking out a new life, off the grid in Wyoming could only carry so much weight or harbor so much investment. Make no mistake though, while this is Wright's first feature she has been behind the camera for multiple episodes of “House of Cards” and, at the age of fifty-four, feels comfortable both directing and anchoring a film that completely deals with her character being isolated with her pain. In many ways, it's curious to wonder what it was about Jesse Chatham and Erin Dingam's screenplay that made Wright decide to take it on as her first feature credit as a director, but in watching the film unfurl it becomes clear the many parallels both Wright and the character of Edee must deal with. Whether it be the element of both situations being a learning experience, the unexpected issues that are unaccounted for, but have to be dealt with, or the fleshing out of the characters, their nature, and the environment around them; these are all things that need to be considered in order for your life or your movie to be fulfilling.

Wright's Edee is a woman dealing with an unbearable loss, a loss and a pain that is revealed in her film in what is Wright's greatest moment as a director in this film. It's truly haunting, legitimately gave me chills, and allows the visual storytelling to do all the heavy lifting with Ben Sollee's actual score only emphasizing these emotions. In Edee's tragedy, she elects to relocate and isolate herself as opposed to being around people who would rather her simply pretend to be better than openly discuss her pain. In this departure Edee will obviously come to realize many a truths about herself, her existence moving forward, and the importance of having people involved in that existence that genuinely love her, but “Land” is largely about the long, complicated road to those realizations and not the moments of realization themself. Wright gives little indication of how much time is passing beyond the natural climate change outside her cabin windows which works in favor of the film's aesthetic but does detract from how much of a toll this is taking on her character. It isn't until a half hour into the film that another sign of life shows up in the form of Demián Bichir's Miguel. Bichir, an actor who garnered acclaim for 2011's “A Better Life” and has turned that into a string of strong supporting roles in major projects, brings his natural charisma at a time when it's needed most. The first act largely integrates Edee into her new setting with many a wordless and sometimes tepid sequences that then pivots to a second act where Edee becomes more comfortable and almost reliant on Miguel visiting her despite having little desire to be around people. It is in the bond that forms between Edee and Miguel that the film hits its stride and cascades into a final act that discovers the healing and serenity it has been seeking from the very beginning if not in an unexpected fashion, but an affecting one, nonetheless.

0 Comments

by Philip Price Director: Azazel Jacobs Starring: Michelle Pfeiffer, Lucas Hedges & Valerie Mahaffey Rated: R Runtime: 1 hour & 50 minutes Knowing nothing of the Patrick DeWitt novel on which this film is based, there was a certain expectation for “French Exit” based solely on its qualifiers of being distributed by Sony Classics, the fact it starred Michelle Pfeiffer and featured Lucas Hedges in a supporting role, as well as being released just in time for awards consideration. With a title like “French Exit” I expected this to be something of a peculiar little domestic drama with a European edge to it. An art film of the upmost degree and maybe, potentially even a little irritating due to its stuffy nature. And the film does begin as much given Pfeiffer is playing this aging Manhattan socialite who we see early in the film rip her son, Malcolm (Hedges), out of boarding school and who continues to live on what's left of her inheritance from her dead husband until she can't anymore at which point, she and Malcolm move to a small apartment in Paris that belongs to her sister, Joan (Susan Coyne). The film is slightly odd in the semantics it goes through in getting Pfeiffer's Frances along with Malcolm and their cat (don't forget the cat!) to Paris, but it's initially taken as little more than the obligatory quirkiness a production of this nature must adhere to. It is when the mother and son duo finally arrive in The City of Lights that things actually begin to truly become...what was that word again...peculiar. Beginning with Malcolm abruptly breaking off a seemingly serious relationship with girlfriend Susan (Imogen Poots) as soon as his mother tells him they're leaving New York and the country altogether to the trip across the Atlantic where they encounter Madeleine the Medium (Danielle MacDonald) who both becomes a more critical character in the lives of our protagonists than expected and immediately understands something the audience hasn't yet become privy to, there is a change of tone and a turning of curiosity.

The heart of the film is the relationship between Frances and Malcolm and how it mines this world of appearance over substance for exactly that; examining if what can be found between this mother and son is actually a connection with meaning or simply the only other outlet Frances could turn to in order to exonerate her societal critiques after the death of her husband. DeWitt, who adapted his own work for the screen, has a certain flair for the absurdity and given absurdities aren't difficult to come by when satirizing the upper class much of this feels like low-hanging fruit, but what separates “French Exit” from its ilk is the surrealism it embraces in its latter half. The forthright nature of the dialogue, the pure insanity of certain plot points, and director Azazel Jacobs' ability to somehow wrangle all these tones through this pedigreed lens that has no issue winking at the camera without literally winking somehow makes it work. The film itself a contrivance of that which it seeks to expose. Insane yet endearing, this dark comedy that initially appears somewhat airless and old-fashioned builds to a biting, hyper-aware experience that Pfeiffer absolutely crushes in regard to target and tone. Valerie Mahaffey as the aloof Madame Reynard is the true diamond here though, as her character is one who simplifies all the film is trying to convey: an individual so accustomed to privilege there is no need for deception and is therefore always her most authentic. by Philip Price Director: Josh Greenbaum Starring: Kristen Wiig, Annie Mumolo & Jamie Dornan Rated: PG-13 Runtime: 1 hour & 47 minutes The formula of two unaware and somewhat dim best friends stumbling into a plot with larger implications than their small, vacuum of an existence can even comprehend but of which they become the only hope in saving the rest of humanity (or at least the rest of the resort town they're visiting) is not a new one, but Josh Greenbaum's “Barb & Star Go to Vista Del Mar,” which was written by and stars the incomparable Kristen Wiig and Annie Mumolo who previously collaborated on “Bridesmaids,” certainly does everything in its absurd power to give said concept a whole new look. Walking the line between completely trashing the small Midwestern middle-aged woman and absolutely adoring everything that makes their quaint, innocent lives so enviable Wiig's Star and Mumolo's Barb are the best of friends and have been so for so long they've kind of morphed into one another or one big, feathered hairdo of excessive sweetness, wonder, and bliss. Their lives have followed similar trajectories to the point they've both ended up working in the same mall furniture store post-divorce, get fired from said store on the same day, and kicked out of their "Talking Club" on the same night for lying about still having those jobs at the furniture store. In what feels like the biggest departure the two could possibly make from their cozy, insulated existence the two decide to kick-off this next phase of their lives by embarking on the adventure of a lifetime by leaving their small Midwestern town for the first time ever.

Arriving in the fictional Vista Del Mar or the oasis of all "mid-lifers" as Wendi McLendon-Covey's Mickey would say, Barb and Star are essentially aliens arriving on a different planet and discovering different forms of life than they've ever encountered before. Chief among these specimens in Jamie Dornan's Edgar who, unbeknownst to our titular heroes, is there at the behest of his Dr. Evil-like boss (also played by Wiig) to enact a revenge plot for some ridiculous reason that doesn't make much sense but doesn't have to because nothing here - except how much you laugh - is taken seriously. All that matters is that Barb and Star are now caught-up in a love triangle, something even more daring and scandalous than leaving their comfortable routine, while beginning to lie to one another for the first time in what is probably the history of Barb and Star. Surrounded by the brightest shades of orange and turquoise possible as well as the largest cocktails ever concocted, our heroines follow the predictable narrative arc laid out before them, but what elevates the film to a different plane of comedy is the specificity Mumolo and Wiig have written with. The jokes - whether verbal, visual, or musical lampoons - each come so quick that they feel effortless, but by the time the entire picture is revealed feel that much more thought-out and almost exquisitely crafted. Dornan nearly steals the movie with the show-stopping "Edgar's Prayer" number that made me laugh harder at a movie than I think I have in a decade if not more. Dornan completely understands the tone of the world he's in and more specifically, how he fits into it. Other supporting players like Vanessa Bayer, Mark Jonathan Davis, Damon Wayans Jr. and Karen Maruyama each add to the bizarre nature of the world this film exists in. Special shout-out to Reyn Doi though, who essentially put me in this movie's pocket from the very beginning with his rendition of Barbra Streisand and Barry Gibb's "Guilty". It's easy to note with its awfully specific brand of comedy that “Barb & Star Go to Vista Del Mar” isn't for everyone, but the ongoing outlandishness of it all and the admitted stupidity is what made the experience such a delight, especially having come along at this point in time. by Philip Price Director: J Blakeson Starring: Rosamund Pike, Peter Dinklage & Eiza Gonzalez Rated: R Runtime: 1 hour & 58 minutes “I Care A Lot” is the type of film that knows exactly what it is and what it means to be from the very first frame. Healthcare workers divvy up monotonous rows of medications into small plastic cups intended to keep their targets as much in check as they do healthy. The first piece of dialogue is a woman's voice seemingly calling the viewer out, "Look at you. Sitting there," she says as she goes on to explain how the idea of "playing fair" is a joke invented by the rich to keep everyone else poor. All of this accompanied by the immediate needle drop of Death in Vegas' 1999 track "Dirge" or what is another word for a "sad song", an elegy. Writer/director J Blakeson (“The Disappearance of Alice Creed”) pushes all the way down on the syringe releasing every facet of his technique into the bloodstream as quickly as he can. From that first moment the tone is fully engaged and every tool Blakeson has at his disposal is being used to elevate the story being told; the film is firing on all cylinders. The difference between “I Care A Lot” and most films that begin with such promise though, is that it sustains its nasty yet overwhelmingly engaging tone throughout its nearly two-hour runtime. By the end of that runtime, one is bound to be both satisfied as far as viewing experiences go, but also somewhat overwhelmed not simply by the lengths the narrative decides to venture, but the implications of our lead character's, the anti-hero in many respects, course of action. It is this course of action, this central scheme that Rosamund Pike’s Marla Grayson has cooked up, that provides much of the propulsion and confidence the film displays throughout as one would require such attributes to pull the type of legal Olympics off that she does here. While the tone is enjoyable - delectable even - and we, the audience are having a blast watching these people do these terrible things there is no escaping the fact that afterward, once the credits have rolled, we're also somewhat appalled at the fact we did enjoy this level of duplicity so much.

How real and damaging the effects of what the character of Marla Grayson is doing here are the reasons Blakeson has chosen to employ that all-knowing and judgmental narration, why he uses bold, primary colors in both setting and wardrobe to heighten the world in which his film takes place, and why he utilizes Marc Canham's electronic-heavy score to give Grayson's actions an edge that, while understanding she's an inherently evil person, still makes her seem cool. It's the age old question of why we root for the bad guy, the villain, and often times it's because we can recognize their flaws in our own, but even Marla Grayson would tell you her only flaw is being too ambitious and too driven and that she finds no fault in doing whatever it takes to get to the top. It's not that these qualities aren't relatable or are the reasons we aren't sympathetic to Grayson come the end of the film, but it's how far she's willing to cross the line in order to make her ambitions a reality that separates the human being from the truly despicable. "Look at all these cash cows on your wall just leaking money into your account one overpriced hour at a time. Good for you. I'm not here to ruin your business. I'm happy for you to keep milking these poor, vulnerable people for as long as you damn well please. Hell, if your whole enterprise isn't the perfect example of the American dream, I don't know what is." This description of Grayson's scheme cuts to the heart of what is being inflicted upon senior citizens who are deemed no longer fit to take care of themselves by the courts and then have their custody awarded to Grayson who drains their savings. She sells their houses and auctions off their possessions to put as much money back into her pockets as she can. She keeps them alive as long as possible in nursing homes run by smug creatures like Sam (Damian Young) allowing her to liquidate their assets for as long as possible so that by the time they die whatever was put in their will to be passed on to their inheritors is essentially gone. It's such a sterling little summary that Grayson herself would seemingly be impressed were it not directed at her. The words come from a lawyer played by the ever-charming Chris Messina at the behest of Roman Lunyov (Peter Dinklage) whose mother has recently become the latest victim of Marla's scheme, but who is not like most clients given Lunyov doesn't much care what a judge or a court has to say or how it applies to his affairs. Lunyov's mother, known as Jennifer Peterson and played by the truly delightful Dianne Wiest (seriously, she's great here), carries an extra amount of baggage that in some ways complicates Grayson's life, but in more ways than one seems to give Grayson the kind of adrenaline rush she requires to keep her motivation and determination at a ten. The routine of securing potential clients from a doctor friend and then stringing these cases through a reliable court as overseen by a familiar judge (a completely in-tune Isiah Whitlock Jr.) in order to obtain guardianship after which Grayson along with her business and life partner, Fran (Eiza González), begin the transfer process of their client to a home and then attain all of their equity and estate is simply to feed the rush and by the time Peterson comes along it is very much a routine that Grayson is prepared to move past. It would seem that, given the film's focus on a legal system that allows a court-appointed legal guardian to defraud her elderly, unsuspecting clients while maintaining the guise she is only present in the best interest of said client, that the outrageousness of the system in question would be Blakeson's primary target, but as “I Care A Lot” plays out and the full picture comes into view it's clear that's not entirely his objective. At one point in the film, Grayson responds to the assertion that she is brave, but stupid by saying, "To make it in this country you need to be brave...and stupid and ruthless and focused. This playing fair, being scared, that gets you nowhere, that gets you beat." This response would have you believe Grayson is willing to do whatever it takes, risk whatever she had to risk - and keep in mind this is a woman who responds to threats against her mother's life by saying that she doesn't care and calling her a sociopath - in order to become wealthy and lead the life she desires. Needless to say, nothing else will be good enough for her and whatever it was in her past that nurtured this drive must have been enough to make Grayson feel that even her own life wasn't worth living if it wasn't how she imagined because she's certainly willing to put that on the line as well. This personal code of conduct by which Grayson lives her life is maybe the most fascinating aspect of the film and is what Blakeson uses to convey his main ideas through which sway more toward the rich and the way their money personifies influence rather than simply taking aim at loopholes in a system that those who go looking for them are bound to find. Rich people use money as a bludgeon and Blakeson, notably a Brit, repeats the phrase "America dream" in his screenplay enough that it would seem “I Care A Lot” is largely an examination of why this type of power and influence has come to symbolize the "dream" of an entire nation. More interesting even is that later in the film during a conversation between Grayson and Peterson, Grayson rebukes what she considers empty threats from Peterson by reassuring her of her stance that goes, "I don't lose. I won't lose. I'm never letting you go. I own you and I will drain you of your money, your comfort, and your self-respect. Not because I want to, not because I'll enjoy it or because I plan for it, but because your people didn't play by the rules." Is playing fair different than playing by the rules then? Technically, Grayson is a woman who plays by the rules, but that doesn't restrict her from bending them to fit her needs. It may not be fair, but neither is life, and at least what she's doing is legal. The difference between Grayson and someone like Lunyov is that she, while doing ethically dubious things, is still on the right side of the law whereas Lunyov - who is in the business of highly illegal actions and has had Lord knows how many people killed - is obviously doing such ethically dubious things on the other side of the law. Yes, it's somewhat ironic that Grayson expects people to play by the rules in response to a scam that takes advantage of a life someone built for themselves only for Grayson to swiftly (and legally) take that away to improve her own, but it is this perverse contradiction of sorts that Blakeson finds both fascinating and something worth exposing. The anecdote about how a bounty for killing cobras in British India then created an incentive for people to breed cobras comes to mind as the chasing of that "American dream" has ultimately led to the breeding of generations upon generations who seek to achieve what they've been conditioned to believe is the apex of an existence by any means necessary. Beyond the heavy themes and weighty commentary though, “I Care A Lot” is a hell of a piece of entertainment that carries the irony of its title through to every moment of its amoral fiber. One could list several dialogue exchanges to exemplify the facetiousness with which Blakeson approaches these serious issues he's discussing though I'd call specific attention to the scene in which Grayson and Lunyov come face to face for the first time. Furthermore, the performance of Pike must be singled out as Grayson, while an anti-hero, is still the character than anchors everything here. Pike has to strike just the right balance of having all these admirable qualities of being intelligent, ambitious, focused, and charismatic while at the same time using those qualities in all the wrong ways and making the character both engaging and contemptible. Never vulnerable and always threatening Pike is more than capable of this type of performance given her most notable turn as Amy Dunne in “Gone Girl,” but Marla Grayson's actions would almost rank as more reprehensible given the consistency of them and how she treats humans as commodities and qualifies how much she cares in a quantitative fashion over a qualitative one. "You're a rare person, Marla." Dinklage's Lunyov tells her and in the final 10 or so minutes of the film, Blakeson ties up his narrative by stressing just how exceptional she is while simultaneously emphasizing the film's most glaring limitation as it rushes to the final stop on the runaway train that is Grayson's success. Not so much a satire as it is a scathing indictment of how twisted the American dream has become, “I Care A Lot” achieves something most films only aspire by feeling fresh and enlightening despite nearly every character being rotten to their core. “I Care A Lot” is streaming on Netflix. by Philip Price Director: Rose Glass Starring: Morfydd Clark & Jennifer Ehle Rated: R Runtime: 1 hour & 23 minutes Hedge your bets. That's the approach everyone, I included, seems to take when waging eternal salvation versus eternal damnation. In writer/director Rose Glass's feature debut, “Saint Maud,” the titular Maud isn't simply hedging her bet though, she's gone all in. As Jennifer Ehle's Amanda discovers early in the film, Maud's conversion is a recent one leading the audience to naturally wonder not only what it was that brought Maud to this new set of revelations, of faith, or of sheer belief, but also why she jumped head-first into the "God-fearing" pool. What is the long, complicated road Morfydd Clark's Maud traveled to reach this destination? While Glass keeps the details scarce and supplies enough so that only the most attentive of viewers might parse together pieces of backstory, what hits and remains the most haunting aspect of this horror film/psychological drama is Maud's belief that putting her well-being in the hands of God is the best choice - especially given the final destination at which she arrives. It should be a safe bet. Everything she's been told about God would lead her to believe she's walking toward the light, but guilt is a powerful drug and it's one the church and religion wield with mighty influence.

Belief systems flourish because they facilitate the interest of those involved - a broad example being a large majority of the population wants to believe in something more after death and therefore latches onto the idea of a God or Gods responsible for everyone and everything - but then comes the question of retention. How do these systems keep believers on the line and continuing to practice the beliefs they share - or more immediately, how do they keep their financial support in check? More often than not it isn't enough to simply go forth and live the lessons of a certain faith or denomination and so the fear of that aforementioned eternal damnation is put in place to keep one in a position of fear, of feeling threatened, or most ironically of all: feeling judged. There is this thing so many believe is the absolute truth, but it's difficult to reconcile why such divine truth would be filled with so many threats and riddled with such tactics of guilt. Maud has seemingly felt judged her entire life, but she has turned to an extreme faith in God in hopes of repenting and being "born again" as the evangelicals like to say. To be clear, there is absolutely nothing wrong with finding comfort or solace in a system of beliefs or an unbound deity. The point of “Saint Maud” is not to discourage, mock, or ridicule such things, but more to target this idea of how guilt and shame are intrinsically linked to repentance and redemption while acknowledging the distortion that can be drawn by a tormented individual; how easily, in other words, what one believes to be a journey towards a truly spiritual life can quickly become a solitary journey into darkness. Set in the stormy, skittish, and windswept atmosphere of the North Yorkshire coast “Saint Maud” begins in the equally atmospheric setting of a dingy, blue-tinted hospital room where something seems to have gone terribly awry. Maud is the nurse in the room, but we don't see the patient. In fact, Glass keeps the viewer's focus trained on little details in the room rather than on what has taken place as Maud attempts to avert her eyes just as much as Glass does the audience's. Fast-forward to sometime after this incident and Maud is now serving as an in-home caretaker to Ehle's Amanda, a "creative type" Maud notes she tends to not have much time for given their typical self-involved nature. Amanda is suffering from stage four lymphoma of the spinal cord which Maud responds to in her prayers (which also serve largely as the film's narration) by stating, "I dare say you'll be seeing this one soon." As Maud is entering this new chapter of her life, she's looking for a purpose, the reason God saved her and, in that search, she finds as much not in taking care of the sick and dying, but in saving their souls. This revelation of sorts comes after Amanda sees the necklace of Mary Magdalene that Maud wears; a religious discussion then ensues. Amanda comments that she was unaware merchandise was made of the woman widely regarded as a repentant prostitute, but in all actuality seems to have been the "apostle to the apostles" for her work alongside Jesus. While Amanda initially questions Maud with both a skeptical curiosity and slight patronizing tone Maud has no hesitation in relaying her intense new relationship with the Holy Spirit. Maud confesses to Amanda that there are times she feels she's physically being inhabited by God, that it's him reassuring her when everything is good. Amanda, sincere or not - Ehle plays the moment in such a fashion it could be interpreted either way - tells Maud about her fears concerning her dying moment. What will she be looking at? Who will be there if anyone? What will she be thinking about? What will be next? Nothing? Maud swiftly reassures Amanda of God's great love, glory, and plan for her as Amanda simply responds by anointing Maud her, "little savior." This is the sign Maud's been waiting on. Maud knew God saved her for something greater than mopping up after the decrepit and it is this calling to be a "savior" that fills Maud with more God's love than ever before. More than enough to share. Adam Janota Bzowski's haunting score immediately sets the tone for Glass' character study- which it is more than anything else - as Ben Fordesman's cinematography mimics the mood elicited by the domineering weather along the North Yorkshire coast. This is to say, that while true with all films, the thought of how the character of Maud might be perceived in real life, without the lens of a genre filtering her actions, occurred more frequently while experiencing this film than not. Likely regarded as an odd individual at work or someone we might be familiar with in passing whose most memorable trait is seeming a little crazy, but whose damaged exterior largely goes ignored in order to make our own lives less complicated, Maud is an individual starved for real affection. Genuine love. While Glass delivers small moments as to the catalyst that took her from working in a hospital to doing in-home care what we never see is any indication of a support system for Maud. No family or friends outside a single character who worked with Maud at the hospital and seems to harbor her own guilt for ignoring the signs Maud was spread too thin are ever mentioned. This is brought up not as a shortcoming necessarily, but more in the vein of curiosity. What is it about Glass' filmmaking that makes the intent more interesting than the execution? There are layers upon layers of ideas at play that deal in the perceived behaviors one must abide by in order to gain access to heaven or how people hold onto certain beliefs out of nothing more than being unable to overcome their guilt and yet none of these ever feel communicated in the nuanced fashion Glass seemingly intends to convey them. In short, the film implies much more than it explores and by the time we reach the (admittedly shocking, but also somewhat expected) conclusion, “Saint Maud” feels like a film chasing after larger implications than its quaint narrative can deliver. Maud's prayers are akin to ecstasy and we see this play out in several instances including a scene where Maud feels the spirit of the heavenly Father in the company of Amanda. Amanda mimics Maud saying she feels His presence as well and Maud, confirming she's as gullible as she seems, takes this as a strong indication of fate. This is fascinating simply by virtue of the fact it tells us just how delusional Maud is or has become, but by having the character of Amanda present and by having her add this layer of disdain we understand there's always been an "Amanda" present in Maud's life and therefore understand how tragic and not just how complicated her life has been. In this case, the narrative ambition lines up with the way in which Glass frames her film, but as Maud begins to willfully hurt herself in order to feel more holy the divide between narrative ambition and what the final product actually conveys grows wider. Maud's actions become increasingly more alarming and while Glass keeps her camera squarely on the pain Maud inflicts upon herself the physical sacrifices begin to overshadow the psychological horrors leading to these delusions. These visions Maud experiences become more frequent after the plot delivers its protagonist a gut-punch from which she'll never return and it's not difficult to correlate said visions with Maud's quick descent into madness given she feels she's failed her mission from God. What the film doesn't do though, is feel like it always capitalizes on the numerous strands of ideological commentary it desires to analyze and investigate. With passing mentions of William Blake, human frivolity in comparison to true spirituality, and existential dread it's clear Glass wanted to deal with the spirit in the sky in a big way, but it becomes boiled down to the idea religion causes as much if not more pain than it does prosperity. This isn't a large complaint and honestly - the movie is probably better off for it - as exploring a single facet of a larger idea is usually a more advisable approach than trying to tackle all aspects of a main idea in a 90-minute period, but it feels inherent to “Saint Maud” that there is more to discuss than what is presented and that lends to some of the disappointment in the final product. That said, this film does contain one of the best, most skillfully plotted jump scares witnessed in some time. In the eyes of the Catholic church, a Saint is someone who displays faith, hope, and charity in exceptional and consistent ways throughout their life with the cruelest joke of all being that despite her devotion, no matter how earnest, Maud's actions in relation to her faith were misguided in such a way one can't help but to wonder where her poor soul ultimately stood in the eyes of God. by Philip Price Director: Harry Macqueen Starring: Colin Firth & Stanley Tucci Rated: R Runtime: 1 hour & 35 minutes Harry Macqueen's “Supernova” opens with a demonstration of what the title refers to: a star exploding thus allowing its molecules and all the other fantastical, unknown elements it's made up of to fall from the heavens. Some of this dust is destined to make its way to the earth where one day it will help to make-up the organisms that populate the planet. An exploding star, a burning love...we're lucky if we experience either in our lifetime. The film fades from this demonstration to the serene, static shot of two men in bed together, their hands intertwined and their love apparent. A crossfade to an overcast sky where pillowy white clouds still manage to somehow pop through pans down and lands on an older model RV where the two men, we first met a moment ago are now on a road trip together. Despite the quick-wit and sarcasm of one Tusker (Stanley Tucci) and the frustration of the other, Colin Firth's Sam, it's already been established this is not a tale of two aging, grumpy fellows on an adventure to sow their wild oats, but rather it is a tale of two lovers hoping to find some peace and solace in what is likely the last moments of their being together. We are first made aware of the reasons for this holiday when Sam stops at a grocery store on the side of the road only to return to find Tusker has disappeared. While Sam locates his partner shortly thereafter it is clear to both men that Tusker's early onset dementia is getting worse at a pace neither was likely prepared for. How could anyone ever be prepared for as much? No matter the amount of time given to process the pain it would never seem to cease. The film though, is a brisk and very tidy 90 minutes and that is all Macqueen requires to paint his sweeping yet pulverizing love story. It's almost astonishing really, how invested we become in both Tusker and Sam despite the brief running time and further, how many moments are absolutely a punch to the gut whether it be in the way Firth's voice cracks when he gets emotional or through as simple a gesture as one helping the other button his shirt. Anchored by these two effortlessly affectionate and grounded performances from Tucci and Firth (but especially Tucci, my God!), “Supernova” is a film about coming to terms with reality no matter how inequitable it may seem and the honest conversations that are eventually unearthed around it. A true portrait of companionship, a meditation on legacy, and the impact it all has on the lives of those most important to us.

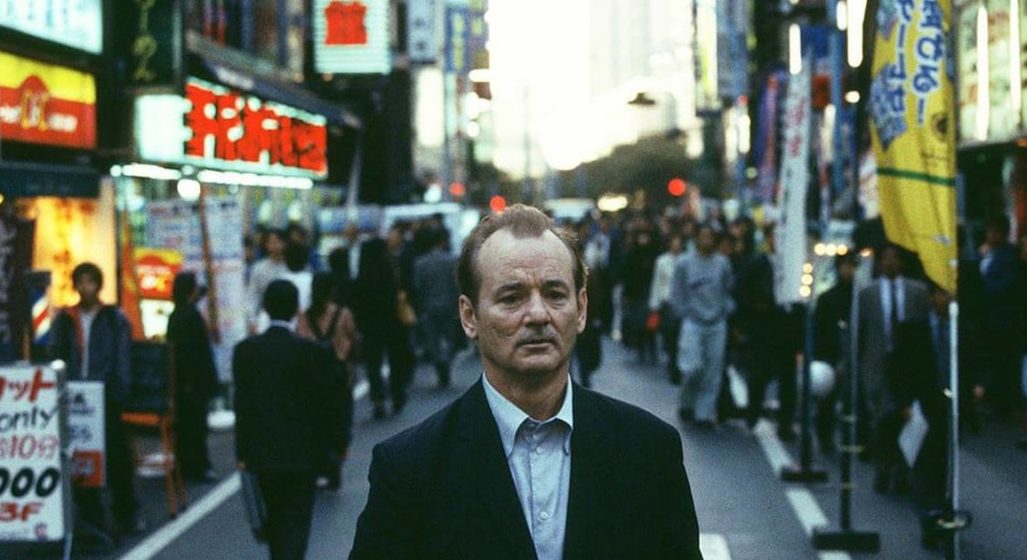

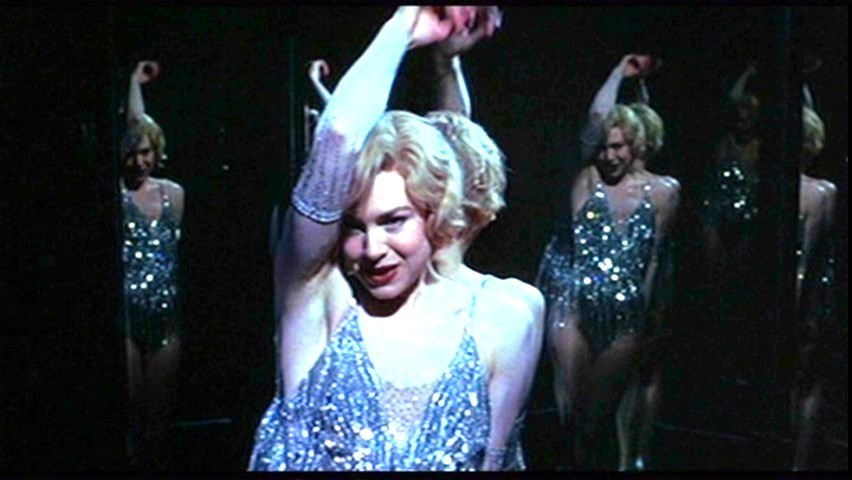

It's difficult to even embark on a journey like “Supernova” given you know the destination is a heartbreaking one, but Macqueen's film is certainly well worth it. Though inherently a narrative that will tug at the heartstrings, Macqueen - who also penned the screenplay - never allows his quaint drama to fall into the realm of melodrama. Despite what is happening to him, Tucci's Tusker is naturally resistant - or at least pretends to be - to the idea he'll eventually be able to recognize even no longer himself. Tusker deflects, putting on as if he's accepting of the idea and taking his fate at face value which is why he will freely go about saying so many things and making so many promises he knows he's either lying about or that he never intends to keep. That said, it's evident from the very first interaction between he and Sam that Tusker is the more ornery, outgoing half of the couple despite quite enjoying his alone time. Tucci, who is always so skilled in being both welcoming while also making you conscious of the fact he's probably the smartest guy in the room begins with Tusker in a place where we perceive him to be something of a cynic and largely insensitive, but it quickly becomes evident how gracious he is with his wit. And so, despite this seeming acceptance of the hand fate has dealt him, Tusker struggles more with the implications of it on Sam than anything else, his beloved, his savior, and the best friend he's ever had. Tusker is intent on not becoming a burden and doesn’t want to reach a point where he feels he’s lost control of his life but is made more aware every day of how rapidly he's approaching that moment. He doesn't want to simply "become a passenger" as he phrases it, noting that "you're not supposed to mourn someone while they're still alive." The way Tusker is very self-effacing and almost glib about his diagnosis forces the reaction one would expect to get from a man who's knowingly losing his mind to transfer to his partner, another reason Tusker doesn't intend to allow this disease to take him to a place he has no desire to go. Sam can't help but hold onto everything. Where Tusker has no desire to become something other than himself that would taint the image of how those he loves remember him, Sam can't help but want to soak up every single second with him and would choose to prolong the inevitable as long as he could. At one point, Sam even pleads with Tusker to not let him off the hook and that he now believes this is part of the reason he was placed on earth; to take care of his husband in these circumstances, to discard what's fair and only focus on the love they share and to see this through to the very end. It's a truly devastating performance from Firth whose aforementioned cracks in his voice are enough to warrant waterworks on their own, but it's interesting for despite Tusker's somewhat averted response to his illness and Sam's more appropriate response it is Firth that gives the more reserved performance. Obviously, this is largely due in part to the nature of the character's, but it's difficult to imagine this dynamic not coming, at least partially, from the 20-year friendship Tucci and Firth shared prior to starring in this film. What assists in Firth's more soft-spoken approach and what balances the chemistry the two stars already have is what Macqueen brings to the screenplay in allowing the space for his actors to develop the characters far past the trip and necessary talking points he has plotted for them. It's made evident early on that Sam's English roots run deep in this relationship with Tusker being from the States, but seemingly adopted by Sam's family as we never glimpse nor are introduced to any of his relatives. Beginning as this modest road trip movie to resolve opportunities missed or skipped in the past, Sam and Tusker drive across the Lake District in North West England to Sam's sister (Pippa Haywood) and her husband's (Peter MacQueen) house where Tusker is set to surprise Sam with a party. It is through the interactions with family members and friends they haven't seen in some time that we see Tusker entrust the well-being of Sam to his brother-in-law, where we see Tusker ask Sam to read a tribute, he wrote to him aloud, and where Sam figures out that Tusker's condition is much worse than he thought. Sam is a concert pianist and Tusker an author with Sam having been under the impression that Tusker has continued writing over the course of their trip, putting the final touches on his latest and likely, last, novel. The pivotal scene comes when Sam looks for and finds Tusker’s notebook and observes the deteriorating state of his writing and therefore his mind but is also sidelined by other revelations that come to light from within this box of keepsakes. It's a truly heartbreaking moment to see this man who has clearly poured the entirety of his being into sustaining his partner for over two years only for, in this moment, the reality of it all to confront him with as blunt a truth as he's seen up to this point. This scene, an hour into the film, also outlines how even in the strongest of relationships there are these tendencies to conceal parts of yourself. Not in a scandalous sense, but more in desiring to preserve the image held of you; it's an act of suppression more so than it is one of deception. No one can know the mind of another, not completely anyway, and as this realization crashes down around Sam one can also see the glimmer of acceptance in this understanding of how best he can handle the situation moving forward, no matter how much it might hurt him. Shot in a very intimate fashion by Oscar-nominated cinematographer Dick Pope and laced with the soothing, piano-based score of Keaton Henson, “Supernova” is a stanza of a movie; a poem of a love story set to beautiful melody. Majestic even. We are taken in by the inherent warmness of Tusker and Sam's relationship and genuinely soothed by the beautiful sights that sweep by outside the windows of their RV. It's a technique that brings us into both the scenario and setting in such a way that we don't want the trip to ever end either; making it all the more painful that it slips away after only an hour and a half. Thus, is the magic of the movies though, even when it immerses the audience in worlds a tad bit more depressing and darker than desired-such as this. What makes Macqueen's film all the more engaging though, is that despite its inevitably depressing ending and darker subject matter, it's impossible to not smile at the light these characters bring to both one another and the world around them in turn allowing the viewer a greater sense of sympathy, compassion, and understanding towards a subject most don't care to openly discuss or acknowledge. It's funny really, how this end of life drama is ultimately inspiring others to go out and live theirs. by Tyler Glover and Julian Spivey Sunset Boulevard Director Billy Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard” is just one of those classic movies about the movies themselves and I’m thrilled it won Best Film at the Golden Globe Awards in 1950 back before the Golden Globes separated the film categories into Drama and Comedy or Musical. Featuring terrific performance from Gloria Swanson and William Holden it’s one of the all-time great film noirs. At the Oscars that year it was beaten by Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s “All About Eve,” which was nominated for a record 14 awards. - JS La La Land And the Oscar goes to "La La Land!" Or wait, it didn't. One of my top five films that won the Best Picture Globe that did not pull off a Best Picture win at the Oscars is at the heart of one of the biggest blunders in Oscar history. When Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty went to present the Best Picture Oscar, they were given the wrong envelope and mistakenly proclaimed "La La Land" as the winner but it turned out the winner was actually "Moonlight." After winning a record seven Golden Globes including Best Picture, "La La Land" felt like a sure thing to take home the Best Picture Academy Award. This musical directed by Damian Chazelle follows Mia and Sebastian as they fall in love while chasing after their dreams in Los Angeles. The movie is a whimsical and romantic film for all of the dreamers out there encouraging us to hang on to our dreams while also showing us there are going to be roadblocks but if we just press on, our dreams can come true. Most of the time, movie musicals are adaptations from Broadway plays but this was an original script meant just for the screen. It made this all the more exciting and all the more worthy of a Picture win at the Oscars. However, it will take a long time for someone to ever break that Globes' record if it ever is broken. - TG On Golden Pond Director Mark Rydell’s 1981 family drama “On Golden Pond” was a masterclass in acting from two of the all-time greats at the end of their careers. Henry Fonda would win his only Best Actor Oscar for his performance as Norman Thayer, in his final film role. Katharine Hepburn portrayed his wife Ethel and Fonda’s real-life daughter Jane Fonda rounded out the terrific cast. “On Golden Pond” would win Best Drama at the Globes in 1981. Hugh Hudson’s “Chariots of Fire” would defeat “On Golden Pond” for Best Picture at the Oscars. - JS Brokeback Mountain Leading up to the Oscars, "Brokeback Mountain" had won tons of critic's prizes for best film and had won the Globe, PGA and DGA. It felt like a shoo-in to win. Even presenter Jack Nicholson appeared completely shocked when revealing the winner to be "Crash." "Brokeback Mountain" was a landmark film for the LGBTQ community. It tells the tragic love story of two gay cowboys in 1960s America as they battle their feelings and trying to do what is socially acceptable at the time. It is a heartbreaking film that reminds us all that love is a powerful and beautiful thing. The Academy was called homophobic and there was a public backlash at the film's loss and it was deserved. "Brokeback Mountain" should be a Best Picture winner at the Oscars and that is a fact. - TG Almost Famous Director/writer Cameron Crowe’s “Almost Famous” is one of the all-time great films to never be nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, but it did win Best Comedy or Musical at the Golden Globes in 2000. “Almost Famous” is loosely based on Crowe’s time writing for Rolling Stone magazine at a teen in the ‘70s and features Patrick Fugit as Crowe’s stand-in covering the fictional band Stillwater. The film also features terrific performances by Billy Crudup and Kate Hudson, who would win Best Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture at the Globes for the performance. - JS Beauty and the Beast "Beauty and the Beast," one of the movies released during Disney's Renaissance, became the first animated film to win Best Picture at the Golden Globes and also became the first animated film nominated for the Best Picture Oscar. On Oscar night, the Best Picture was named as horror classic, "The Silence of the Lambs." While the merits of that film cannot be questioned, it would have been "beautiful" if this film would have taken home the Oscar. "Beauty and the Beast" follows Belle as she becomes a prisoner of the Beast in exchange for the release of her father, Maurice. While living in the castle, Belle starts to fall in love with the Beast. The Beast is actually a cursed prince who has to have the love of someone before the last rose petal falls on his 21st birthday or he will remain a beast forever. The film managed to win two Oscars for Best Original Song and Best Original Score but it would have been great for it to pull off a Best Picture win as well. Since the Best Picture nomination for “Beauty and the Beast,” two other films ("Toy Story 3" and "Up") have also reaped bids. This year, "Soul" is hoping to join that club. - TG Lost in Translation Films like “Lost in Translation” are why I’m occasionally happy the Golden Globe Awards choose to separate its best film categories into Drama and Comedy or Musical because terrific films like director/writer Sofia Coppola’s film about two lonely Americans who become fast friends in Tokyo almost never win Best Picture at the Oscars, though it was nominated. “Lost in Translation” features terrific performances from Bill Murray, who won Best Actor in a Comedy or Musical at the Globes, and Scarlett Johansson, in one of her earliest roles. The film was beat by the juggernaut that was “Lord of the Rings: Return of the King” for Best Picture at the Oscars. - JS Moulin Rouge "Moulin Rouge!" is the film that got me interested in award shows in the first place. After watching "Moulin Rouge" and hearing of its Golden Globe nominations, I became interested in seeing if it would be able to translate any of those nominations into wins. On the evening of the Globes, "Moulin Rouge!" would go on to win Best Picture-Musical/Comedy and Best Actress for Nicole Kidman! I had become obsessed with this movie to the point of watching it multiple times and listening to the CD in my car everywhere I was going. I was wanting it to win the Best Picture Oscar! However, on Oscars night, "Moulin Rouge" would have to settle for two Oscars for Art Direction and Costume Design. "Moulin Rouge" tells the story of Christian, a penniless writer in early 1900s France who falls in love with a courtesan named Satine while trying to put on a play funded by a Duke that also is in pursuit of Satine's affection. "Moulin Rouge" is also the film that got me interested in movie musicals in general and also had me looking into the musicals of the past as well. I really wish "Moulin Rouge" also had a Best Picture Oscar to go with its Best Picture Golden Globe. - TG The Descendants At the time I was probably disappointed that Alexander Payne’s “The Descendants” won the Golden Globe for Best Drama over Martin Scorsese’s “Hugo,” and I’d probably say “Hugo” is still my preferred film of the two (I haven’t seen either film again), but that was such a great year for film pretty much all of the nominees would’ve made for great winners (I still haven’t seen Steven Spielberg’s “War Horse” though). In his Golden Globe-winning performance George Clooney plays Matt King, an attorney in Hawaii whose family has entrusted him with 25,000 acres of land and the decision on whether he should sell it for a fortune or keep it, all while trying to raise two troubled daughters by himself after his wife suffers an accident that has her in a reversible coma. It’s a tour de force performance by Clooney and a well-crafted film by Payne. - JS Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri The 2017 Oscar race was an interesting one. "Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri" won the Globe for Best Picture, SAG and the BAFTA but had to settle for the nomination being the reward on Oscar night. "The Shape Of Water" ended up winning Best Picture that year and it has really stumped me as to why. "The Shape of Water" was an interesting film but "Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri" was a brilliant piece of art examining the lengths we go through to right a wrong. In this film, two-time Oscar winner Frances McDormand plays Mildred Hayes, a mother hellbent on justice for her daughter who was raped and murdered. She rents three billboards that question the police as to why nothing has been done and no arrests have been made. As a father myself, it is heartbreaking to watch Mildred on this journey but in a way admiring her for her tenacity in her journey for justice. I can't say that in her shoes, I would not do the exact same thing. 'Three Billboards' would win Actress and Supporting Actor on Oscar night but it should have won the Best Picture Oscar as well. - TG

by Philip Price Director: Fisher Stevens Starring: Justin Timberlake, Ryder Allen & Juno Temple Rated: R Runtime: 1 hour & 50 minutes I was raised in the South, in the middle to lower class though much closer to the lower than the middle with strong religious views imbued from my mother’s side and a versatile education environment that schooled me on cultures and classes outside my own. I bring this up not to highlight necessarily the point of view from which this review will be written, but more to say that movies became an outlet by which I experienced parts of the world I thought I'd never visit. Movies helped me meet different types of people I might have never met otherwise and they helped me gain different and varied perspectives that likely would have never crossed my mind without them. Perspective is the key word here as seeing through someone else’s eyes is important, but so is seeing different situations the world may throw at you as handled by someone you recognize. This brings us to “Palmer.” While the latest feature from actor/director Fisher Stevens may not seem the kind of revelatory product to change someone’s world view it may have very well done just that for me were I to have seen this film some 15-to-20 years ago. “Palmer” doesn’t inherently feel like the groundbreaking sort because it does in fact feel rather familiar, but everyone has to get familiar somehow and needless to say, “Palmer” isn't a bad way to do so. Stevens' film, as written by Cheryl Guerriero, utilizes its familiarity to affectionately illustrate its well-meaning message and when I use that word I use it intentionally as Guerriero's script never makes mention of any key words or phrases (except for maybe "queer", I guess) specific to the issues the movie deals in, but rather it simply shows us - through action and interactions - that love is easier to come by than hate no matter who you are or where you come from. Purposefully set in the north shore of Louisiana (and primarily shot in Tangipahoa Parish), the premise of “Palmer” as it deals in a child saving an adult as much as that adult ends up actually having to save the child is as well-worn as the time-loop premise at this point, but the humbling details of how said premise comes to fruition are what consistently push the film toward the kind of acceptance our titular character could only hope for regarding his young counterpart. That said, it's not difficult to see where the movie will end up or even how it will get there, but the one-two punch of Justin Timberlake's solid yet restrained performance along with newcomer Ryder Allen's aura of absolute sweetness make “Palmer” exactly what it was intended to be: a simple reminder of what really matters in a world where such heart is easily lost, which, feels like a reminder we could all use these days.

Timberlake plays Eddie Palmer who was once upon a time a college football star at LSU but was sent to prison for 12 years with part of the narrative intrigue obviously being around what it was that sent him there. At the beginning of the film, Palmer has just been released and returns home to live with his grandmother, Vivian (June Squibb), who more or less raised him alongside his father after his mom abandoned him. Vivian is God-fearing, but common sense-wielding Louisianian who is as happy her grandson is home as she is keen on him securing a job as soon as possible. Vivian is also adamant Palmer join her at church every week which is where he first meets Sam (Ryder Allen), the young boy who lives in the trailer next door to Vivian and who Vivian cares for and takes to church with her when his drug-addicted mother (Juno Temple) disappears for days or even weeks on end. One wants to believe Temple's Shelly (whom Palmer quickly has a drunken one-night stand with) does in fact love her son, but she clearly has a more than manageable amount of her own issues and addictions she needs to deal with. Naturally, Vivian's house has become something of a safe haven for Sam and while Palmer is initially somewhat irritated by both the seeming attention paid him by his own grandmother as well as by the fact Sam has tendencies of not conforming to his biological gender, things happen abruptly that force this dynamic to evolve. Yes, Sam likes to play with dolls, wear barrettes in his hair, and dress like a princess for Halloween and Palmer - clearly unaccustomed and uncomfortable with these tendencies - questions Sam's awareness that he is in fact a boy. When Vivian unexpectedly passes away in the midst of one of Shelly's extended benders Palmer is left to care for Sam on his own. In a somewhat ironic turn of fate, the only job Palmer is able to secure is that of a school janitor allowing him to not only look after Sam while at the house Vivian had made home for both of them, but throughout the day as well. It is in these daily observations where Palmer sees the treatment Sam endures from bullies - often the spawn of his own idiot high school friends that haven't evolved much either - as well as the kindness lent him by his pretty (and divorced) teacher, Maggie (Alisha Wainwright). What ensues is what was referenced earlier in terms of the familiar tropes concerning Sam allowing Palmer a measure of growth and purpose; these changes therefore giving Palmer the strength to rescue Sam from his situation. Stevens executes said archetypes with such humility though, it's impossible to not be endeared to the arc of it all. Of course, the draw here is Timberlake who has taken some time since his last live-action role and understandably committed his time to music projects and the animated ‘Trolls’ franchise. While he appeared in a supporting role in 2017's Woody Allen feature “Wonder Wheel” (also starring Juno Temple) Timberlake has otherwise been absent from the big screen since his 2013 dud, “Runner Runner.” In many regards, the jury is still out on Timberlake as an actor. He's had some critical wins - most notably in smaller, supporting roles in films like “The Social Network,” “Inside Llewyn Davis,” “Alpha Dog” and “Black Snake Moan” - whereas in films where he's taken the leading role a la “Friends With Benefits” (though personally, this is one of my favorite comfort movies), “In Time” and “Trouble with the Curve” it would seem each has proven to either be a critical or commercial misfire. Essentially, Timberlake simply hasn't experienced that breakthrough that might allow him to solidify his presence as an actor as much as he's been able to do on the music side of things. Granted, that's a big ask for anyone given Timberlake's musical credentials, but with “Palmer” it feels like the multi-hyphenate is getting closer than he's ever been before if not completely there yet. His turn as the eponymous character in this latest endeavor is by far the most substantial opportunity, he's been given in a leading role capacity and it seems he was aware of as much going in. The character of Palmer is at the heart of almost every scene yet Timberlake knowingly doesn't go for broke under the weight of the movie resting on his shoulders. In fact, he does the opposite by commanding the screen not with all the flash of his music video persona or the charisma baked into his ‘SNL’ appearances, but rather by remaining stoic and conveying this strong, guarded sense that is conveyed mostly through his silence. Palmer is a very matter-of-fact guy given the presumed nature of his nurturing and these context clues help explain how the character not only landed in prison in the first place, but why he's remained so diligent about starting fresh even if that means starting from the bottom. To a great extent, Timberlake uses only his eyes and their sideways glances in order to get at the heart of what a relationship, new or old, might mean or impress upon him. The heart of “Palmer” lies in the core relationship between Timberlake and Allen's Sam though, and it is the winning chemistry between the two that heralds the inclusive nature of it all (when it very easily could have been the other way around) and the embracing of those who are different by looking at them for what they bring to the table and not how they detract from it. Speaking of Sam, this is a kid who is content being who he is. He does what feels natural and is comfortable in his own skin. Sam isn't aware of what others consider odd, but part of “Palmer” focuses on the painful ways in which he's made aware some people won't accept him for who he is or who he wants to be. Allen, in his debut feature performance (which is pretty crazy given his pension for authenticity), makes you fall in love with Sam immediately. While Timberlake's Palmer is undoubtedly the steadfast anchor, Allen's Sam is the hope beneath the sails and the young actor effortlessly carries that dynamic by delivering a convincingly honest performance in both the comedic as well as the more dramatic moments. Other supporting players like the great June Squibb and TV-regular Alisha Wainwright do well to prop-up the two leads as Squibb is largely a vehicle through which the movie emphasizes the contradicting nature of the environment we've been dropped into where the church serves more as a water cooler than a place of worship whereas Wainwright's Maggie helps to balance the Palmer/Sam equation. Maggie helps guide Palmer to the conclusion of just how critical his presence in Sam's life is and it is through these actions a romance naturally evolves between the two adults who are both seeking a kind of redemption. Sam lends Palmer this sense of purpose, a new level of self-esteem, and in turn, Palmer is able to give Sam a father. Of course, just as all seems fine and dandy the third act rears its ugly head and Guerriero pulls in the melodrama to plot the perfect ribbon that will wrap the story up cleanly. It's a little antithetical, especially given so much of “Palmer” wears its low budget like a badge of honor; it’s rough and rural locations echoing the grit of both the setting and the characters, but the formula works because the emotions are so genuine and because the intentions are so well-meaning. The formulaic nature is also made to work because of that aforementioned collision of two worlds that seem unlikely they could ever be cordial with one another. The film never criticizes Palmer or Sam, but instead allows the material to breathe and their actions to make the case for the film as opposed to big, sensational speeches. Nothing here feels forced or artificial despite the hot button issues clearly incorporated into Guerriero's screenplay to relay a specific message. This story of two unlikely people coming together is nothing if not exactly what we need right now and, again, while the beats may feel familiar to some the message should resonate with all. As a story about someone who, through adversity, can come out the other side and be better for it one can only hope such an admirable arc might open the eyes of those unfamiliar with this formula to new and varied perspectives and hell, maybe even a few who've seen this story before as well. “Palmer” is streaming on AppleTV+. by Philip Price Director: Shaka King Starring: Daniel Kaluuya, Lakeith Stanfield & Dominique Fishback Rated: R Runtime: 2 hours & 6 minutes As we get older, we become more conscious of our time and the legacy we might leave. The long game no longer feels as long and therefore the implications of our actions become just as important as the ramifications. On the day of January 15th, 1990 William O'Neal was a 40-year-old man who'd been drinking with his uncle into the early-morning hours of Martin Luther King Day before running into westbound traffic on an expressway and jumping in front of a car that killed him. His death was ruled a suicide. Later that night, on PBS, the second part of the 14-part documentary series, “Eyes on the Prize,” would debut. The second part of the series chronicled the time period between the national emergence of Malcolm X in 1964 up through to the 1983 election of Harold Washington as the first African American mayor of Chicago. Included in this span of time is the year 1969 and in 1969 William O'Neal would turn 20-years-old. That year is also the year a 21-year-old Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, would be assassinated. “Judas and the Black Messiah” tells the story of how these two men were connected to one another in a tale as old as scripture as indicated by its biblical title.